Stefan Roigk: ‘Bursting Confidence’

March 13, 2014 § 1 Comment

From March 14th until April 12th, RESONANCE partner Le Bon Accueil in Rennes, France, hosts the second installment of Stefan Roigk’s installation Bursting Confidence, a work that premiered last summer in Kunsthaus Meinblau in Berlin, Germany.

It was only at the end of the summer that I got the chance to talk to Stefan about his – and more specifically this – work, when we met early one rainy grey afternoon in his small studio in a nice old big school building in Prenzlauer Berg, a locality in Berlin that nowadays is the southern part of the borough of Pankow.

Then and there, all of Stefan’s Bursting Confidence was inside a pile of cardboard banana boxes…

He opened them up…

“I use papier-mâché for this piece,” Stefan explained. “That is great material and very easy to work with. And the other thing is: it is not heavy at all. All together these boxes weigh, maybe, 50 kilos… That’s really light. Fortunately. Because of course I wanted to hang them and that would have been pretty difficult had all of the objects been kind of heavy…”

Is it the first time that you work with papier-mâché? Did you have other material in mind before?

“Yes, it is the first time. Before I was thinking of silicon. But that is too heavy. It would have been really heavy to have these parts in silicon. As you can see, the thing that I did is… I used packing materials… plastic packings, wrappings, plates, cups … all sorts of packing material and stuff that I found. Actually, I have been collecting all of my trash. For two years, I kept my trash…”

You collected all of your trash for two years…!? But that’s fantastic…!

“Yes, yes, yes! But only the plastics. All the plastic forms.”

Two years of plastic trash…!? That must have been a LOT!

“Oh yes, it was a lot. All these menu boxes, chocolate things, cups for drinking, plastic plates… But it was great to have a lot of different forms. Because what interested me was the ways in which I could combine them. I combined a lot… plastic cups, and things like that… I combined all of that trash into forms. It was like firing up Pro Tools and then cutting and combining sounds.”

How did you make the papier-mâché prints?

“Let met try to explain… Take a plastic plate, the sort of thing that you get to eat from at parties, or when you’re having a pick-nick. I would take it, press it, tear it, deform it… and then put it in the papier-mâché… I used buckets filled with the papier-mâché. I would push in the forms of my trash, by hand. And then mold it. I had the whole studio full with forms and material! Originally I also wanted to make the papier-mâché myself. But, you know, that is a lot of work! If you want to make papier-mâché yourself, you first have to cut the paper. Then you need to put the slices of paper into water. Then you have to add glue. And then, after that, you have to take it, and use a lot of pressure to transform it into plates. Then it has to dry again. And then you have to shred it. It is a good work to do, but it is a bit too much. So I just went to the store, and bought the papier-mâché that they sell in boxes.”

A sort of ready-made papier-mâché?

“Yes! It is ready made. You only need to add water. And it’s really, really nice! A bit like plaster. You can get very thin forms. They remind me… of distortions. It is a lot like distortion on audio material! And though it looks like plaster: it doesn’t break like plaster. When you throw it to the ground, it doesn’t break. So I could hang it just with little holes in it. We drilled holes in the papier-mâché prints, and they didn’t break…”

“Combining the forms was a lot like doing music. I first wanted a lot of forms. Like when you do music, you want a lot of sounds. The real structure of the piece then emerged when I hung it in the room. So I prepared sets of smaller structures in the papier-mâché. We combined these, in the end, in the gallery space. We used nylon strings to hang the forms. You know, the nylon strings that one uses for catching fish. In the fishing shop they also showed us how to make the special knots that we needed, because we had to get all the knots in one single piece of string, in order to be able to do it while the string was already hanging. That was not easy. But in the shop they learned us a knot that made that possible. So we first did a lot of knots,” Stefan laughed… “And then we hung the forms.”

“My first idea for the piece was to create a structure like a storm. Something that is coming from the ground, and then flies up to the top. But what I really wanted was to built something like a musical structure. And that does not fit with a structure that originates at the ground, and then goes up. Because that would be something that you could only walk around. And not a structure in which you can follow the lines. You would mainly see the ground part, and the rest would be far away.”

So you wanted a temporality? A timeline?

“Yes. The strings had to be fixed from one wall to the other. So the idea is that you can follow such a string. Which is like a timeline. Time starts in one point, and while you walk through the room, you will see how the pieces change. How the relations between the forms change all the time. There are many different points of view. The strings change, The direction changes. Sometimes the forms together will add up to a sub-structure. And sometimes they will seem separated, just because you take another point of view. That again reminded me a lot of music. It is like walking inside a musical piece when it is presented in a sound editor: you can separate the tracks or choose to see them mixed together.”

Then the sculpture is like a 3-dimensional musical score.

“Yes. The molds combine into small structures. Like musical themes. And there are repetitions. Like with these plastic things that they use to put your salad in at the kiosk. It becomes like a rhythm. And it changes… first there’s 2 parts, then there are 3, again 3 parts, 4 parts, … 3 … and then 1, and it hits the wall… It is actually easier to discern these kind of rhythms when you look down at the installation, from above. And of course the idea was also that the lines are somehow like the lines on note paper.”

“Two trash things I used very often, because I really like them: these plastic plates and the cups. First of all, because they were easy to recombine when I did the moldings. They were really nice to cut and then to make something out of it. For the idea was: first I have these structures, and then I put some of them together. It is like when you record single sounds and then, afterwards, in your sound processing software you combine the sounds. And then it becomes one.”

They are also very recognizable, as forms.

“Yeah. Funny thing: many people asked me whether my idea was to make a work about trash… Well, maybe it was. But it was mainly forced, because I actually very often use these kind of sounds. And this time I wanted to have them also as sculptures…”

“There are 8 little loud speakers that play back 4 different stereo tracks in between the papier-mâché forms. The speakers hang inside of the structure. They are part of it. Just like the speaker cables. Often I use a sort of electricity cable as speaker cables, but this time I used normal speaker cables. Because they look more like the nylon strings. And I let them just follow the lines. They built lines, comparable to the lines that the nylon strings build. The loudspeaker itself is grey. When you stand inside the installation you can of course see that it is a loudspeaker. But because of its color it becomes part of the structure.”

“The sound itself is really concrete. They all come from microphone recordings, of paper and of all of these plastic things that I molded; the plastic cups, the plates and other stuff like that. Afterwards I selected parts, and did some digital treatment, for example by shifting the pitch. But not very much. I didn’t change the sounds very much.”

So a lot of the sound originates in the same plastic objects, the same trash that you used to make the papier-mâché forms. And the paper? Different kinds of paper may make very different kinds of sound.

“That of course is true. But I actually used mainly cardboard; and cardboard objects, like cups. And then indeed the plastic things. I played all of them with me hands, and recorded a whole night long. The material that I recorded lasted, maybe, I think, 10 hours.”

“The actual sound of the installation comes from an 8 track loop, made out of 4 stereo tracks. After one hour the sound piece repeats. One of the stereo tracks indeed lasts one hour, but it is pitched; originally it maybe was ten minutes. The other three stereo tracks last 20 minutes, so for the one hour loop these are already tripled. They are loops inside the loop.”

“In my previous works, the sculptures often had a somewhat artificial look, I think. They were like minimal art or something. But the sounds were concrete sounds, like in this work; it was concrete sound material. So the combination of a sound with the objects was more conceptual. There remained some sort of a gap between the sculptures and the sound. This time my idea was to bring the sounds and the sculpture really together, by letting them come from the same source. It actually was a big step for me.”

But the link between the sounds and the sculpture – the idea of a ‘music’ and a ‘score’ – remains abstract. That is a concept. That is not concrete …

“It is not a real score, no. But the idea of 3 dimensional and graphical scores is central in my work. For this I was, I think, inspired by artists like Jackson Pollock. When I saw Jackson Pollock, for me that was like a graphical score. A score which you can think of as having an endless time. It transcends the borders of the frame. It is really like a sound installation! And I wanted to put these kind of structures and forms in the room, in a space.”

Did you ever consider asking musicians to interpret your works? And then look at the sculpture as graphical scores, and play them?

“Oh yes, of course I did. And it is kind of nice. But, for myself, I have no real interest in producing music out of it. It is rather the idea of a score that interests me. On the one hand I like to produce graphics, on the other hand I produce sounds. And sometimes I like to combine them. Then it is an installation. And when you visit an installation and focus on one point, that is the now. The spot where you focus is now. And then, when you move, as a viewer, you are making a timeline for the piece. Because of your moving and the your shifting focus.”

So each viewer is putting her own time into the piece?

“Yeah, sure. Of course. I like to say: the viewer becomes a mixing board for the piece. Because the piece is continuously changing while the viewer is walking inside.”

But will not also the soundtrack suggest certain movements to the viewer? People tend to react to sounds. They might be tempted to walk from little speaker to little speaker, in order to ‘close listen’ to each of the channels, one after the other.

“That may be true. But the sound actually is changing very slowly. You can have the experience a little bit slower as well. You do not have to hurry to get to the sounds!”

“It is a main theme, I think, of sound art, that you fill the room with one structure. Which is not repeated all the time, but still, in a way, the dynamics and the proportions of the sound will be mostly the same all the time. When you go to a Rolf Julius piece, it is certainly not the same all the time. But after a minute, you will know what it sounds like… So the idea for my sculptures is, in a way, related to that of drawing: how do you fill the paper?”

“All the sonic material for this piece has more or less the same frequency shape. There is not too much droning stuff. And there are not many high frequencies. I use these sounds because I think that their materiality fits the papier-mâché. With its white, or light grey, color. For me sounds have a kind of color, and a structure and a form. Like sculptures. So all the sounds that I use here are quite light; but not too much. They are all grey. Light grey. And not too dramatical. The sounds are not very haunting, or stuff. And I did not use real voices.”

“The night that I recorded the sounds, I played them with some sort of a dramaturgy. Like this sound of a plastic bag, I wanted to have it playing very slowly in the beginning, with a very low volume; and then getting louder. So I recorded these types of dramaturgical sequences. And afterwards I did not cut in the dramaturgy. What also was important for me, was that a certain sound would only be represented in one place. (Or in two places, because everything is in stereo.) I did not want sounds to change places; the sounds are just in one spot.”

“Originally I wanted to make a very dynamical and cut up piece, with a lot of changes. I was considering something really haunting; psychedelic sounds, really heavy, like the soundtrack of a horror movie. And I thought of using a lot of singing as well, a bit like Nurse with Wound, or stuff like that. But when I saw the light grey material hanging, I knew that this was wrong. This wouldn’t fit. It would have been too… yes, let’s say: too much! Because the sculpture is not so different in all of its pieces. And it is a very light thing. Hanging, even…”

“So that is why I called the work Bursting Confidence: at first I was thinking of this really mind-changing, maybe even frightening, psychic installation. Of something exploding; and it should be an exploding mind!”

The piece still gives you the impression of an explosion. Frozen at some point in time. Like a still from a movie.

“Yes, but as I started working more on the piece and on the idea, it got softer and softer… It still is an explosion, but it is not so dangerous anymore. It became more like a molecule, where you zoom into with a microscope, and then encounter all of these smaller structures, of atoms, stuff and things…

It still is an explosion.

But it is soft.

It is more soft…”

…

Stefan Roigk – Bursting Confidence. Sound installation at Le Bon Accueil, 74 Canal Saint-Martin, Rennes, France. From March 14th until April 12th, 2014. Vernissage: March 13th, 18h30.

Exploring the almost-impossibilities between art and science.

September 9, 2013 § 4 Comments

Last in the series of new sound art works commissioned by the RESONANCE Network in the 2012-2014 period is Photophon, an installation by the Belgian artist Aernoudt Jacobs. As small and fragile as it laborious, Photophon will premiere as part of the RESONANCE-in-Maastricht showcase that is taking place between September 13th and 29th at Intro in situ’s. (The exhibition in Maastricht will also include a new installment of Signe Lidén’s Writings and another presentation of The Beaters by Thomas Rutgers and Jitske Blom. Peter Bogers will present a second version of his Untamed Choir and David Helbich made an arrangement of the performative soundwalk that he composed for the Flanders Festival in Kortrijk, for the streets and squares of Maastricht.)

Photophon is based upon the so-called photoacoustic effect, that was discovered in the late nineteenth century by the brilliant Scottish scientist, inventor and innovator Alexander Graham Bell, who probably is best known as the inventor of the telephone. As a teenager Alexander Bell witnessed how his mother slowly grew deaf, which aroused his very special interest in all things related to speech, hearing and sound. In 1880, together with his assistant Charles Tainter, he developed a device that transmitted sounds wirelessly, on a beam of light: the photophone. It reflected sunlight from a flexible flat mirror that actually served as a microphone. When somebody talked against the mirror’s back, the variations in air pressure caused by the soundwaves of the voice moved the flexible material, and were literally reflected in variations of the brightness of the mirrored sunlight. One then ‘only’ needed to translate these back into sound…

It was while working on this receiving end of his photophone that Bell discovered the optoacoustic or photoacoustic effect. He found that solid materials that were exposed to a beam of sunlight that was interrupted by a fast turning wheel with slots (thus giving rise to a very rapid series of light pulses), started to produce sounds. The main (though not sole) reason for this is photothermal. The physical explanation goes roughly like this: the material is heated by the light energy that it absorbs, which causes it to contract and expand; these ‘movements’ of the material then give rise to pressure changes in the surrounding air; but that of course means that there will be sound!

It was this use of strictly ephemeral phenomena to create sonic events that inspired Aernoudt’s artistic re-interpretation and development of Bell’s discovery. “I was mesmerized by the idea,” he says, “that sounds around us can be created with light. From Bell’s research notes I learned that any material comes with a sonority that will be revealed by hitting it with a strong enough beam of light. Every material has a resonant frequency, but every material can also be ‘sonically activated’. And its sound is directly related to its resonant frequencies. For me this was a revelation, touching the world of sounds in its very essence!”

Aernoudt’s work is a fine example of a combination of artistic and scientific research. He has been developing his Photophon installation in close collaboration with the Laboratory of Acoustics and Thermal Physics of the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium. I saw a prototype (picture above) of the elegant and intriguing horn-like object that is to become the sounding heart of the installation, when earlier this year, at the IMAL in Brussels, I visited an exhibition of Overtoon, the Brussels based platform for research, production and distribution of sound and media art that is directed by Aernoudt and Christoph de Boeck.

“The horn is the last in the chain of elements that together make up the photophonic object that I imagined,” Aernoudt explained. “It acts as a loudspeaker. Because of its specific dimensions, it will amplify some of the frequencies produced by the photoacoustic cell that I built. That cell is a kind of Helmholtz resonator, placed at the narrow end of the horn. Eventually, the horns will be between 60 and 70 centimeters long, very narrow at the one end (about 3 millimeters), and then widening to some 22 centimeters at the other end. The precise dimensions are related to the resonance frequency that I work with.”

“In the very first version I used the horn of an old gramophone that I bought on a flea market. The light source was a green laser. That Photophon produced a soft buzzing sound. The subsequent versions use customized horns, that are adapted to the cell. All is centered on one specific frequency, with its corresponding over- and undertones. I started with a plastic horn, realized in one piece using a 3D printer. But that was too fragile. It broke rather quickly. The model at the IMAL exhibition also has a plastic horn made with a 3D printer, but that was done in 3 separate parts, that I then glued together.”

At the IMAL I saw light, I saw movement, but I did not hear any sounds.

“True. But that’s because the light source was a led, which is not intense enough to produce a sound that is audible with your bare ears. There is a sound, but you would need to use a stethoscope to hear it. With a laser source, that I can use in my studio, the sound becomes audible. So for the RESONANCE installation in Maastricht, I will use laser sources.”

And you will use glass horns. Glass surely has acoustic properties that are quite different from those of the plastic you used for the earlier versions. This will also influence the sound, I presume.

“Yes, it will influence the sound. The glass will resonate more than the plastic. And of course there is the visual, the aesthetic aspect. The transparent glass horns will make for a far more delicate look than that of the the opaque white plastic objects.”

How did your collaboration with the Laboratory of Acoustics and Thermal Physics at the KUL, the Catholic University in Leuven, come about?

“We have been working together for about one year and a half now. Our collaboration started after I had invited them to come to one of my earlier exhibitions. At the time I already was researching the sonic and acoustic investigations that were done in the 19th century, and the empirical sound theories that were developed at that time by people like Hermann von Helmholtz, Rudolph Koenig, Jules Lissajous, and so on. I was particularly intrigued by the fact that in many cases those investigations were based only on acoustic phenomena, with no electronics involved. They analyzed everything with analog, mechanical devices. It makes their findings very palpable and understandable. Christ Glorieux, who is the head of the Leuven Acoustics Lab, introduced me to Bell’s photophone, that they were working with a lot at the laboratory. And this then gave rise to the idea of making an installation based on the photophone.”

“Art-science collaboration are sort of a trend these days. So my case is surely not unique. It is very interesting though. Also, because it is not always easy to really work together. Unlike a scientist, as an artist I am all the time groping around in the dark. As an artist, that is where you want to be. Where you need to be. You will always want to try out things that are deemed to be ‘impossible’. Putting a horn on a photophone was one of those ‘impossibilities’… The scientists at the lab would never use a horn. They put tiny microphones inside the acoustic cell. Which, from their point of view, is far more manageable. It is what they need for their scientific approach. But still, sometimes there are holes in their research…”

Which then will allow you to jump right in.

“Indeed. And we can talk about it. That makes for very interesting conversations.”

Do you have a scientific background yourself? Or is your scientific knowledge self-taught?

“Most of it is self-taught. But I did study architecture, which introduced me to many different subjects. A lot of technology. But also mathematics and mechanics. So that makes for quite a broad background. Even though I never finished my studies. I failed the fourth year, after which I stopped and decided to concentrate on music and art. But also as a musician and an artist, I never stopped thinking about space.”

What is the role of space in the Photophon installation?

“It is important that the space be as quiet as possible. It also will be important in the sense that it will determine the way in which visitors approach the installation.”

In Maastricht the Photophon installation will be made of three of Arnoudt’s photophonic objects. Each of them will have a laser light source, with the intensity necessary to produce audible sounds. “The continuous laser light is interrupted by two rotating slotted wheels. These wheels are the second element in the construction,” Aernoudt explained. “Each of the wheels is moved by a small electric motor. There are two of them (separated by a distance of about 5 centimeters), in order to provide two distinct modulations of the laser light. If the first wheel is rotating at a very high speed, the sound produced by the photoacoustic cell will be a continuous túúúúúúúúúúúúúúttt. The second wheel is meant to interrupt that continuous sound, so as to produce a kind of rhythm: túúútt – túúútt – túúútt – túúútt – túúútt … The third element of the object, after the laser and the wheels, is the photoacoustic cell that I designed, and which – as I explained before – is based on the idea of a Helmholtz resonator. It is a small sphere, containing a black disc. Because of the series of light pulses that is hitting the disc, the photoacoustic effect will give rise to a sound. Now the shape of the cell, the globe, is important because it will strengthen certain of the frequencies. What you will hear, then is determined by the rotating wheels, and by the properties of the photoacoustic cell. The Helmholtz resonance and the acoustic properties of the glass horn, the fourth and final element in the construction, take care of some form of amplification of the sound.”

I guess it would be possible to add some sort of a controller to the electric motors that drive the wheels, to change the speed of their rotation in real time, and thus vary the resulting sound in real time. You might then play the Photophon like a musical instrument.

“I absolutely intend to provide a certain kind of ‘musicality’. But in the form of an installation, not in the form of a playable instrument. The musicality is latent. It is present, but hidden. The electric motors are driven in real time by a micro controller, which will give variations and rhythms to the tones. And each of the glass horns will actually have slightly different dimensions. Being handmade, it was impossible for the glassblower to make them perfectly identical. I still have to try them out, but I suspect that volume and resonance frequency will be different for each of them.”

So the sounding result will be like a microtonal chord?

“That is difficult to say at this point. A lot will also depend on the precision and the stability of the electric motors that I am going to use. Only if these can be adjusted very precisely will I be able to produce truly microtonal structures. But as things are looking now, that will not yet be the case in Maastricht. I hope, though, to be able to develop the work further in the near future.”

“As I said before and although this may not be immediately apparent: the musical, the compositional element, is very important to me. But I will only be able to fully exploit this in some next phase of the project. I am already planning a sequel for next year, which would be an outdoors installation. It will be based on the use of sunlight, but combined with new technologies that will enable me to track the sun, and then add artificial light as a compensation as soon as the intensity of the sun becomes insufficient. This confrontation of 19th century technologies with the top technology of our times is, of course, already evident in this version of the work: the laser, the drive of the wheels, the cutting of the wheels… All of this is based on very contemporary technologies, that then combine with these pure, non-electric, analog ideas from the 19th century. That’s amazing, I think. It’s a meeting of two very different worlds and two very different times…”

…

Aernoudt Jacobs’s Photophon can be experienced at Intro in situ (Capucijnengang 12, Maastricht, the Netherlands), as part of a RESONANCE showcase including works by Peter Bogers, Signe Lidén, David Helbich and Thomas Ruthers & Jitske Blom.

The opening will take place on Friday September 13th, 2013, at 17h00.

The RESONANCE exhibition at Intro in situ can be visited daily from Saturday September 14th until Sunday September 29th, between 11h and 17h.

There will two special guided tours by Harold Schellinx (on Thursday September 26th and Friday September 27th, at 19h30), and a lecture on sound art by Armeno Alberts, on Thursday September 26th, at 21h30.

…

![]() “Phonophon” was produced for RESONANCE by Stichting Intro in situ in Maastricht, the Netherlands, with additional support from the Dutch Province of Limburg.

“Phonophon” was produced for RESONANCE by Stichting Intro in situ in Maastricht, the Netherlands, with additional support from the Dutch Province of Limburg.

The work was developed by Aernoudt Jacobs in collaboration with the Laboratorium voor Akoestiek en Thermische Fysica (Laboratory of Acoustics and Thermal Physics) of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Catholic University of Leuven).

The work was developed by Aernoudt Jacobs in collaboration with the Laboratorium voor Akoestiek en Thermische Fysica (Laboratory of Acoustics and Thermal Physics) of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Catholic University of Leuven).

Peter Bogers’s “Untamed Choir”

July 25, 2013 § 3 Comments

The past couple of weeks in Østre (the Lydgalleriet’s new space for sound art and electronic music in Bergen, Norway), Dutch artist Peter Bogers has been working on the installation and fine tuning of Untamed Choir, a new work that he produced for RESONANCE, and which will premiere as part of a short summer-exposition at Østre (from July 25th until August 11th, 2013), also featuring The Beaters, by Jitske Blom and Thomas Rutgers.

Peter Bogers’s new work is a spatial composition that uses 30 vocal tracks, played back through a set of 40 small loudspeakers that are hanging from the ceiling of the room into which the piece is projected. 20 of these are positioned on a large circle, with their cones pointing inwards. The others are spread over the rest of the projection space.

The following picture shows a sketch of a possible positioning of the loudspeakers, but the precise distribution of the speakers will obviously depend on the properties and dimensions of the room in which Untamed Choir is presented.

“Up until now the installations that I made, were more like sculptures; visual things; things that are,” Peter said. “The visitors might contemplate them and listen to them for as long as they liked. This is sort of a first time that I present a work that actually has a definite beginning and a definite end. Untamed Choir is a composition, a thing with a fixed duration. Of fifteen minutes.”

“The installation nevertheless does have a strong visual component. It consists in a projection of images of noise, moving between white dots on a black background and black dots on a white background, that illuminate the space into which the piece is projected. These images are of a ‘positive’ and of a ‘negative’ kind, just like one might consider ‘screaming’ to be the ‘sonic negative’ of ‘singing’ or ‘chanting’. The projection thus reflects the transformations: from ‘screaming’ and ‘crying’ to ‘chanting’ and ‘singing’ to ‘screaming’ and ‘crying’.”

How did you go about collecting the vocal material that you needed for the work?

“Much of the material consists in samples. Of singing, of choirs… I took anything that I could get hold of and that I thought might be useful. And then there are parts that I sung myself, and parts that I asked friends and acquaintances to sing. Originally I had planned to do a lot of the necessary vocal recordings in Bergen, in cooperation with a number of students here. But unfortunately, due to several changes in the work schedules, that has not been possible. So I ended up doing most of the recording and collecting of the sound in Amsterdam.”

“The things that I recorded myself were primarily related to the many transitions that I needed, in various tonal pitches, between the crying/screaming and chanting/singing. Often such transitions had to be very, very gradual. So gradual, that it becomes impossible to pinpoint the precise moment of change… In the singing parts I aimed at a very stylized… eh… well, yes, I may indeed just say: at a kind of ‘beauty’. I wanted it to be the sort of thing capable to seduce the listeners.”

Many of the fragments that I heard, in your preview video (which you will find embedded at the end of this article), struck me as almost Wagnerian in atmosphere…

“The singing had to be beautiful. Parts of it – including the end – are indeed kind of ‘dark’, kind of ‘heavy’. And some parts get kind of ‘psychedelic’… The piece has been conceived as a single, continuous, expiration. I removed all the breathing from the samples and the recordings. And I distribute the 30 vocal tracks over the 40 loudspeakers. This allows me to actually move sounds in the space. I can make them go round in a circle; and I can freeze them, keep them in one specific spot. Most of the singing is located everywhere in the space, including the circle; but the screaming is concentrated within the circle. When the chanting turns into screaming, the transformation initially takes places within all of the channels. But then gradually it is pulled towards the center. Until the scream occupies nothing but the middle of the room, where it literally is running around in circles. At varying speeds. So it is a pretty … yes … physical work.”

And with the extensive spatial configuration, the listener, when moving around, will experience a continuously changing perspective?

“The idea indeed is that one moves through the space, and that one will encounter changes in the sound on, say, every square meter. But these changes and these shifts are very subtle. They do ask for some concentration, so it may help if one closes one’s eyes… I am actually very happy with the acoustic conditions that I have been given here in Østre. My studio in Amsterdam is a bare space, with a lot of reflections. Here the sound is muted. And that is what this piece needs, because it allows for a far more precise localization of each of the sounds.”

Along with the noisy images that illuminate the space, also a running time code is projected. What do the numbers refer to?

“The numbers actually do not refer to anything specific. It is just a counter that is running, all through the piece.”

Like the transitioning noise images, they seem to suggest, though, that there is also something rather formal about the piece; in contrast maybe with the expressionistic – the untamed – ‘romanticism’ of the singing; ánd of the shouting…

“Maybe… I have to confess that I still have my doubts about the use of the counter. It will be part of the show here in Bergen, but I have not yet made up my mind as to whether I will also include it in the subsequent renderings of the piece… But there is a system to the numbers. When screaming transits into singing, the noisy projection simultaneously transits from positive to negative. So if at first the images are very light (white noise on a black background), then during a transformation from screaming to singing the picture will gradually turn into something very dark (black noise on a white backgrond). And the tipping point will correspond to the counter’s transition from plus to minus. Via zero. The counter also indicates the beginning and the end. When the work begins, the noisy image will just show you the dots, standing still. The dots do not move. And the counter is at 0. Untamed Choir then starts with a scream. And at the same time the counter starts running. The piece ends fifteen minutes later with a transition from low singing to very low screaming, which eventually turns into a kind of sigh, while the counter runs to 0. There it stops, in a still image of noise…”

“So there is a beginning. Then there is an end. And in between it is a cycle.

Like a life cycle.”

“My earliest fascination, in the 1970’s, was for performance art, with its very challenging physicality and direct confrontation with the audience. Around that same time, the first handy video cameras became available, and I realized that I actually preferred this use of technology, as an intermediary, between myself and the audience. I specifically remember one of these early works, of which no documentation has survived, but which was crucial in my development. I was sitting on a chair, surrounded by lights, making sounds with my mouth directly in front of a camera. The close up image of the lighted inside of my mouth then was shown on a monitor above my head, along with the amplified sounds – I started with baby like gurgling and vocal noises – that I was producing. That was how I began apply technology as a means to put up a separation between myself and the onlookers.”

It also shows a very early fascination for the human voice.

“I did an awful lot of recording of the vocal sounds of my first born son. Babies just begin to make noises. It’s a very free form of vocal experimentation, something that I find absolutely admirable, really. And then language starts sneaking in. This transition I find extremely fascinating. I made a work in which I imitate the sounds he made. There are two images, on two monitors. One showing his sounds, and on the one above there’s me. And the alternation of the two produced this very strong rhythmicity… So, yes, the human voice has continued to be a focal point.”

Your background is quite obviously in the visual arts, but do you consider yourself to be, nevertheless, in some sense, a composer?

“Actually I think that music is the best there is. So, to be honest, I really would have liked to be a musician…”

Do you play an instrument?

“Ah, well, a little bit of everything, one might say. I have a pretty good sense for rhythm, so I can do some drumming, play a bit of mouth organ. Nothing properly, though. But sound always had a strong presence in my work. It is only now though, with this work, that some sort of composing is involved. That I find myself being concerned with decisions about pitch, frequencies, timing, the combination of voices, and so on. With real musical components. Before, my point of departure always were the images. But when you turn on a camera to capture images, you also get the sounds. And I always have used this immediate link between image and sound. I would never add a soundtrack to images just to create a certain atmosphere. Sound that is being used to manipulate the viewer into a certain mood while looking at images usually makes me feel pretty uncomfortable. There has to be a connection between the two, a natural link.”

There is quite a long tradition within music and sound art of works that quite specifically address the distribution of sound sources and musicians within a space. Is this something that you have looked into?

“No, not really. I have to admit that my historical knowledge is pretty limited. Especially when it comes to this field of ‘sound art’, which as a matter of fact is sort of new to me. Even though some of my works, in hindsight, actually might very well be labelled as such. ‘Heaven’, for example, a work from 1995, installed in a little working-class house in the center of Utrecht. I had a great many of these old, small black and white surveillance video monitors, which were scattered around the three rooms. And each of the monitors showed an image lasting no more than one second, playing forwards and then backwards. With the corresponding sound, playing forward one second, and then in reverse for one second, on and on and on, in endless repetition. These were all sorts of images of small things, that you might see happen in such a house. Someone’s neck that is turning this way, one second, and then back the other second. And the second hand of a clock, going one tick forward and then one tick backwards again. A baby sucking milk from his mother’s breast. All the time there’s this repetition, this back and forth, and it becomes like a machine, something very rhythmic, going… ta-duh ta-duh… ta-duh ta-duh… which makes it, in a way, highly oppressive. So like ‘Untamed Choir’ this was a piece in which the spatial distribution was central, and the visitors had to walk through the piece.”

“The title ‘Heaven’ is that of a Talking Heads song. Heaven is a place where nothing ever happens. That’s a wonderful image. When this kiss is over it will start again. It will not be any different, it will be exactly the same. Heaven is a place where events do not devalue. Here on earth, for us, that is not the case. And maybe that is indeed our problem.

Things continue and repeat.

But they will hardly remain fun.”

Peter Bogers – Untamed Choir | Thomas Rutgers & Jitske Blom – The Beaters. Two RESONANCE sound art installations presented by Lydgalleriet at Østre, Skostredet 3, Bergen (Norway). From July 25th until August 11th, 2013.

…

The following YouTube clip gives you a 4’50” preview / walk-through in stereo, of Peter Bogers’s Untamed Choir.

…

Playing with your ears

May 11, 2013 § 5 Comments

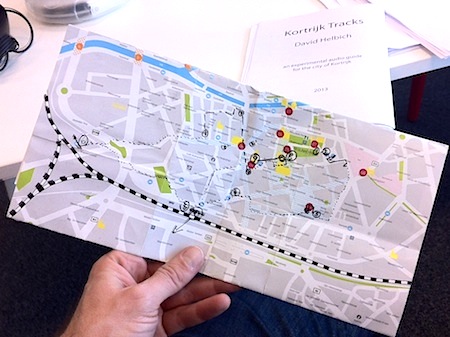

[ david Helbich’s Kortrijk Tracks. A soundwalk. ]

“Louis the Sun King made a number of very strict scores for garden walks. He laid down, in Louis Quatorzian French, how precisely one should walk through his garden in Versailles. Louis walked with his entourage through that garden. And where the Sun King stopped and looked to the left, everyone stopped and looked to the left. So here’s this very complex garden, and it appears to be quite a different one when you are in this place and look to the left, or when you go a bit further and look to the left. There’s different perspectives, other details, other things… This kind of let’s say: absolutism, is something I love to play with. It is the composer, the artist, who decides when and where you will have this, or maybe rather that, experience.”

“The second of my Kortrijk Tracks is called The Garden. It is a track for the Houtmarkt. Which is a square that is called the ‘wood market’, but in fact is just a parking lot. There I put to use Guy Debord’s situationist technique to find your way somewhere, relying on a map from a very different place. Like stubbornly consulting the map of Paris while walking through a German forest. I project part of one of Louis the Great’s garden maps onto that parking lot and ask the users of the guide to move over the Houtmarkt along those lines, as precisely as possible. As a result, already at the outset the audio guide’s absolutism gets undermined. Because the situation there will not allow you to do so, at least not exactly. The place is full of cars. So you are forced to make your own decisions. “

“There is, of course, a touch of irony: ‘this Houtmarkt must have been such a sweet little square, and now they turned it into a parking lot’ … But a parking lot has its own kind of beauty, with its geometrical play of drawn white lines, delimiting the paths and spaces where cars are allowed to ride and stand.”

Which gives it a certain very formal quality.

“Exactly. It is like a score for the movement of cars. And drivers adapt themselves. They might simply ignore the lines. But they hardly ever do. They all stick to the choreography.”

David Helbich was born in Berlin in the early 1970s, and has been living and working in Brussels for more than ten years. Starting out as a composer (he studied composition with Daan Manneke in Amsterdam, and in Freiburg with Matthias Spahlinger), David soon manifested himself also as an installation and performance artist, as a choreographer and as a conceptual artist, while his main field of action gradually moved into public space. All of these interests and disciplines converge in Kortrijk Tracks, an audio guide commissioned by the Flanders Festival in Kortrijk and the RESONANCE Network.

“I started writing for air guitar. This means that as a composer, I left out the instrument. I wrote the piece for a guitar player, but it actually put me right in the middle of movement theater (bewegingstheater) and gave me a link to Fluxus, which I have always felt strongly attracted to. At the same time I remained attached to contemporary music, and in practice I ended up somewhere in between. So I asked myself: what if you would really compose these performative actions, instead of just developing them from movement? What if you’d write them down as scores? So I continued to be a composer, but left out the instruments. Somewhat later I started to do performance theater, with sound and movements. I worked with a dancer, and I let the audience move around: ‘Have a look at her here, and then go have a look at me there’… I was still composing, arranging things in time, putting them in a certain order. But what actually excited me most, was the movement of the audience. As a result, I left out more and more material. All that music. All those media… I was fed up. I didn’t want them anymore. I had already stopped using instruments, and now I also no longer wanted video beamers, no more slides, no loud speakers … I wanted nothing but an empty space, but then had to reflect upon what there was left for me to do. So I walked around with people in a theater. I continued to think of this as composition, because I still strictly organized things. But ultimately this was more about us being our own material, which is something you will also find at the heart of my audio guide. Then finally, at some point, I said to myself: ‘Hey David, you are still working inside a theater! Why not get rid of the theater as well?’ So I stepped outside…”

Like but few others David is aware of the rich history of his field. Between October 2006 and January 2007, he organised in Brussels a series of 12 Walks, each of which related to a different concept taken from the history of walking in the arts.

“What especially mattered to me in the context of those walks, and which also is central to my Kortrijk Tracks, is that you have to be aware that, in a manner of speaking, ‘you never walk alone’. Whatever form you choose, you are never alone with your medium, with your form, with your content. You are always part of this immensely complex world. So you have to find out how much of that world you want to let in, and to which extent you want to lock yourself out in order to do your art. That complex world is the outside, but it also includes the audience. And the agreement – I like to call it a ‘conspiracy’ – to get involved in … well, yeah, in a work of art. In what I sometimes call ‘the offer’. The word ‘soundwalk’ of course is deceptive. For it always is also a walk-walk and a visual walk, it is a traffic walk, an architecture walk and an urbanism walk. And it is a social walk, as in general you will be with a group of people. So you are walking next to who? And how is the group moving?”

A couple of years ago in Brooklyn I participated in a soundwalk where the participants were led through the streets blindfolded.

“I myself have worked with earplugs. Because the more you are shielding off your ears, the more you will be focusing on your hearing. And obviously also when blindfolded you are not walking by your ears alone.”

Touch becomes very important. We were going hand in hand, like a little train.

“I find some form of minimalism to be essential. I offer but little, which makes the experience all the greater. That’s my minimalist principle. The world is chaotic, but what I offer is highly structured. In that sense I am still very much composing. Those walks were usually very strictly timed… ‘and then we go to the left, and then we are here, and then there is another group coming from that side, suddenly crossing our path’ … That’s a score. But there are no ‘offers’. Like actors that suddenly appear and do something. I will not suddenly come out and say something, or show you something… I say nothing. I show nothing. The thing is showing itself. That’s because there is a context, a framework. It makes the audio guide far more than just a piece of sound art. Above anything else, it gives you a context for very different experiences and a very varied focus on a town. And it all starts with the decision to go to the tourist office and pick up a set of headphones, an mp3 player and the book.”

The sounds that we hear in the headphones, are they sounds from Kortrijk? Or do they originate in very different places?

“I want to think of them as functional sounds. There’s a certain number of effects that I like to create. Some of the sounds are field recordings that were made at a number of different places, but there’s also recordings made in Kortrijk. This is related to a basic technique that I already usesd in the very first audio guide that I made, in 2008, together with the Belgian composer Paul Craenen. We recorded the streets in the vicinity of the art workspace (kunstenwerkplaats) in Elsene (Ixelles), with binaural microphones. The idea for the sound walk then was to have people listen to a street while they were walking in that same street, thus effectively doubling the sound scape. It’s a very simple method, but one that creates a fascinating shift.”

You are walking in the street and you hear its sounds. And simultaneously, over the headphones, you are listening to a sonic transposition in time of the very same spots in that very same street.

“You do not know whether the car that you are hearing is real. You think someone is passing by, but when you look, there’s no one there. Or the other way round: you hear somebody walking and think it’s the recording. But then suddenly a real person appears. This corresponds head on to the reduction that I am looking for: the reduction of material, the reduction of composition… You reduce all intervention. And the result no longer is a composition, because you simply are listening to that same street. But again, it is very strictly organized. I then used this principle in an audio guide for the Elsensesteenweg (Chaussée d’Ixelles). This is a busy, quite narrow and sloping street in Brussels. A lot of people get off the bus at the foot of the slope and walk to the tube station at the top. Often that will be quicker. The bus regularly gets stuck in the traffic. This struck me as a particularly funny social phenomenon that I wanted to make use of. The audio guide should, in some way or other, relate to the city. Then, pretty soon, I mix in other field recordings. First these are sounds from the neighborhood, like from inside a shop somewhere along the street. It will give you the impression that you are listening through a wall, because the basic track continues to be a recording of the street’s sounds. This confusion somehow opens up a space. As soon as you are no longer sure about what you are hearing or what you are seeing, as an artist I can do to you whatever I like. I actually prepare you to become receptive to surprises, because you are no longer sure about what is real and what is not. And then I add more exotic field recordings, from Caïro and other Arab cities, which (for example because of the Islamic prayers) have a soundscape very different from that of Brussels. So people start their walk in Elsene, and in the course of some fifteen minutes, via Caïro I lead them back to Elsene.”

It reminds me of your installation Public Sound, which was part of last year’s Flanders Festival in Kortrijk. There you had two loudspeakers mounted at the top of the gate of the Begijnhof, and played back recordings that were made in Nablus and Jerusalem.

“Indeed. One of the Kortrijk Tracks is based on that installation. It uses the same sound material, but in combination with a little choreography that tells you how to listen to the sounds. ‘Walk around the tree, stand still at a certain spot…’ The title of the track is Holodeck, please. You remember that? The Holodeck in Star Trek? It is no more than an empty space, but it will give you the illusion of a virtual reality. It will fool you into thinking that you are somewhere else. This also was the crux of my Public Sound installation. You find yourself standing inside this Begijnhof, but are given the impression that there’s a different city on the other side of the wall. The Beguines that used to live there always stayed within the Begijnhof’s confines. They only heard the city outside. Its sound was all they had.”

“When I started to work on the audio guide, my first idea was to limit myself to this technique of audio doubling and to pick a number of places where this technique would be the most effective. I never wanted to make one continuous walk. It’s more interesting to choose a number of different spots, and make more specific relations with the city. I even thought about sending people outside, to the outskirts. Because an audio guide has to be more than just an mp3 player with a set of headphones and a set of sounds to listen to. It should be a tool for much more than only sound art. It gives you reasons to do certain things, reasons to act. I can send someone somewhere to go. But then what should happen when he or she gets there? This I where I began to radicalize things. And because I found there was still something missing in my idea for an audio guide, I decided to accompany it with a booklet, which to each of the track adds a score, a set of instructions for performative actions at that particular spot. This is how I obtained a very close relation between the Kortrijk Tracks and the rest of my work.”

So what you offer is much more than just the listening to tracks via a set of headphones, at selected spots in Kortrijk. There’s a number of other, very different, activities involved. Each track comes with very explicit instructions on how to listen, how to move, where to stand, what to do…

“There are nine tracks, and nine places. The walk starts at the tourist office. From there it makes a helical movement, which leads you in a number of steps to the center of the city. And each of the nine tracks tries to redefine the meaning and the potential of an audio guide.”

“Three of the tracks – one in the beginning, one in the middle, and one at the end – are exercises. They are called Warm-up, Keep-warm and Cool-down. The first is meant to warm up your ears, the second to keep them warm, and the final one is kind of a finishing off. They emphasize the fact that this is all about your ears; though it remains to be seen whether that indeed always will be the case. For the Warm-up, the beginning of the walk, I composed the gestures of mounting your headphones. You carry them to a small hill in front of the tourist office. It’s a spot where you can look out over the city. There you begin by warming your ears. You’ll need both hands free, so you put the headphones down. You then bring your hands slowly closer to your ears, press you hands against them, and so on. This is of course a highly conceptual way to prepare a soundwalk, leading up to this grand gesture of: now, now it begins! You pick up the headphones, you very slowly put them on, the track starts playing … and then what you hear is the sound of hands that manipulate a set of headphones. It’ll make you very aware of the fact that you are wearing this… thing… this plastic contraption. So here I directly address the materiality of the headphones, and the idea that you have to push buttons, that you will follow instructions. In a way it explains what an audio guide is. I explain the machine, then the audio guide, and finally the situation of you walking through Kortrijk. So this makes for quite a bit of reflection and self-referral. But of course it will not always be as pure as in the first track. After having enjoyed this fine view of the city and the Begijnhof, for the second track you turn around and within seconds will find yourself in the middle of the parked cars on the Houtmarkt. Or maybe it’s the garden of the Sun King’s Versailles. And so you spiral onwards through Kortrijk, from one place to another, through a shopping mall, across the Schouwburgplein, the Grote Markt, the Begijnhof, the parking in the Magdalenastraat, the busstation… There you perform what everyone else is performing: you stand and wait. And like quite a few others that will be listening to music on their iPods, you are wearing headphones. The difference is that you are not waiting for a bus. You wait for nothing. But it is only you who knows. So in fact you are cheating. But then, well, first of all nobody cares, and second nobody will notice. You have become an integral part of that particular situation. It is an act of perfect integration.”

“I had a related experience as a young man in Paris. I was waiting for my father, who was there for work, and I had some free time to spend. I loved Paris. I was from Bremen, it was a beautiful day, there were all these people speaking a language that at the time I did not speak myself, and it was all like… Maybe you know the feeling: you are in a city that fascinates you and, especially when you are still young, you very much want to become someone who’s at home there. You almost envy all those people that know all the unspoken rules and to who all of this is nothing special. So I tried to integrate. For those couple hours I wanted to become a real Parisian. I threw my jacket over my shoulder and began to walk fast, like everyone else. I stood and wobbled impatiently at pedestrian crossings, waiting for the lights to turn green, so that I could rush over to the other side. I was in a hurry, like everyone else. I was going somewhere, and I had to get there as quickly as possible. Well, I was not going anywhere, of course, but this is how I adapted myself to the city, to the situation: this is where I am, there is where I’m going… And during these few hours in Paris, people just kept on stopping me and asking for directions. It was hilarious. Suddenly I was no longer a tourist, I was someone who belonged there, someone who knew his way around. I found myself integrated in Paris… But I was just acting. And the same holds true for the audio guide. When people are walking around wearing headphones and holding a booklet, the world for them has become a theater. But it is also a stage. And they are the actors.”

David Helbich’s Kortrijk Tracks premiered at this year’s Flanders Festival in Kortrijk, as part of Sounding City‘s RESONANCE showcase, and as part of a collection of soundwalks for the city of Kortrijk, curated by the Festival’s director Joost Fonteyne. Currently the collection comprises David’s walk and Christina Kubisch’s ‘Electrical Walk Kortrijk’. It will be extended over the coming years (also see The Art of Soundwalk).

Throughout the year, these soundwalks are made available at Kortrijk’s tourist office to visitors of the Belgian town. David will also adapt his soundwalk for a number of other European cities, where it will be presented as part of upcoming RESONANCE events.

The Kortrijk Tracks make use of ‘pretty generic locations’, and David invites everyone to try the tracks in the city of their choice. You can listen to them and download the full set on Soundcloud, or using the player below. On his web site you can download the accompanying booklet with maps, instructions and scores, as well as a brief manual on how to use the tracks with an mp3 player.

For our Dutch and Flemish readers: this month’s edition (#115) of Gonzo (Circus) Magazine comes with Klankstappen (Soundsteps): a collection of eight downloadable soundwalks in Belgium and the Netherlands, which includes the Kortrijk Tracks and a re-enactment of the first ever Dutch soundwalk. Klankstappen is accompanied by an essay in the magazine on the history and meaning of the soundwalk, written by Danae Bos.

Holes, caves, archives and inscriptions

May 1, 2013 § 7 Comments

At the time of this conversation with Signe Lidén about her ‘Writings’ (an installation commissioned by the RESONANCE network, that premiered at this year’s Flanders Festival in Kortrijk, Belgium, as part of the Festival’s Sounding City sound art program), the space that would come to host the work, on the Buda tower’s ground floor, had nothing in it and still was little other than a hole, a cave, a cavity in the former brewery building: a floor, a ceiling, three concrete walls and a fourth one, made of glass. With words and gestures Signe tried to evoke an image of how that ‘cave’ would look like in a few weeks time. Not an easy task. But in this case it was an appropriate one. For holes, cavities, caves – ‘things’ that are both nothing and not nothing – are key elements in Signe’s work.

“Holes are a fascinating phenomenon. They consist of nothing, they are nothing in themselves,” Signe explained. “Holes are always defined in terms of their surroundings. Holes are matter-less. We perceive them because of the matter that surrounds them. And it is in this sense that a hole nevertheless is not a no-thing; it is not nothing. This is part of what I’m trying to come to grips with. I try to understand what this not nothing is. A hole has more in common with a material object than something abstract like, for example, a concept. Holes are localized, they are somewhere in space and time. A hole has dimensions, a form and a whereabout.”

“Throughout history holes and caves have functioned as time capsules. The earliest works of art were made and found in caves. But also these days works of art are being created in caves. Caves have always been places for religious and magic rituals. Because they offer protection. But also due to their acoustics, which transforms the sound of voices. And of instruments. Because of the way in which holes and cavities filter sound, I very often choose these types of places. In different holes sound has different qualities; it gives the surrounding another kind of layer, or the feeling of really being in that place.”

Holes are time capsules… This also refers to the fact that many important archives are kept at a safe distance from the turmoil of our big cities, where bits and pieces of our culture are stowed away, hidden indeed, in ‘holes’ and in ‘caves’. During much of the Second World War, for example, Rembrandt’s painting The Night Watch was kept safe in a limestone cave not far from Maastricht. Also the Voyager Golden Records spring to mind, that in 1977 were put in a spacecraft and sent off into space, which, of course, is the ultimate hole…

Over the past couple of years, Signe was inspired by a number of rather special ones of these manmade time capsules. Like the Global Seed Vault in Spitsbergen, sort of a botanical Noah’s Ark halfway between Norway and the North pole, where the seeds of as many as possible food crops are being preserved. And Onkalo, a repository for nuclear waste, which is currently being built, deep underground, on an island in the southeast of Finland. Or the Temples of Humankind in Damanhur, Italy, a ‘new age’ complex of caves and tunnels, hand-dug between 1978 and 1991 and filled with murals, sculptures, mosaic and strained glass with motifs and structures inspired by religious and occult societies from all over the world, dedicated to the divine in man and the preservation of spirituality. “I find that very special,” said Signe, “for how do you preserve spirituality? Pictures of these Temples of Humankind show some sort of a spatial choreography, in which all imaginable religious and spiritual images collide, in a kind of mega-kitsch ballet. But the question continues to fascinate me: how could one preserve intangible things for the future?”

Signe’s most recent source of inspiration is a mysterious Archive of Invisibility and Lost Knowledge (she doesn’t know its actual name, and invented this one herself), located in the vicinity of Yangshuo, China. It is dedicated to the storage and systematization of knowledge about traditional crafts, literature and art, that was lost during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). “As with the Temples of Humankind also here I asked myself: how would you do that? How do you save knowledge that has gone extinct? It is no longer there. So is it written in books? Is it in drawings, maybe? Are there still traces? I have been trying to figure it out, but it is very difficult to get information. I sent a number of mails, but didn’t get any answers. So the question remains: can you keep the knowledge of a craft without keeping the objects that it produced? Can you keep what surrounds a thing, without keeping the thing itself? Is it possible to preserve the aura of a work of art, without the actual work?”

Then the thing or the work of art becomes a hole itself…

“Yes, without the thing one would say that there no longer is any material memory. You disconnect memory from matter. If you make something, then there is the thing that you make. But there is also the ritual of the making. The thing corresponds to the technical part of its making; the ritual corresponds to the non-technical part. Does the non-technical part maybe generate as much material memory as the technical part? But then how can you preserve that kind of knowledge, which is not pronounced, but experienced knowledge? Knowledge that relates to ritual, to a practice? Who or what creates the aura of a work? This is the starting point for my Resonance installation. ‘Writings’ wants to be a work about material memory, without creating something that is specifically material. Its focus is on the process, and the process is something without an end. What is being created, remains unfinished forever. It opens up a field of continuous molding, without a final result. It is the idea of inscriptions as a ritual. But also as something auditive. What you hear is part of the things that happen. And visitors will obtain an auditory access to the interior space of the things they are looking at. But for this they will have to move to smaller, separate, spaces within the space.

Do I make myself clear? Do you understand what I mean? “

Could you describe the installation as you now envision it?

“The space in the Buda tower is particularly suitable for this work. Long and narrow, and with a large glass wall. Outside, in the small garden that you can see through the windows, I want to do an archaeological exhumation. In the garden’s soil there must be a lot of things that come from the old brewery. The result of this exhumation of course is a hole, a dug out space, that you can see from the inside, through the glass wall. Inside I will make piles with the sand and soil that I dig up outside. On the ceiling of the space there will be an electromechanical construction, with chains driven by gears of different sizes, which will cause movement in different directions and of different durations. This time aspect is very important. The mechanism will drive circular plates, from which sticks are dangling down. The sticks touch the sand piles. Via their movement they will shape the piles; a shaping that, at the same time, is a writing. They inscribe, they make inscriptions, leave traces. I will put (contact) microphones onto the sticks. The signals from these microphones are sent to boxes attached to the walls. There will be four of them. In one of the boxes there will be a score, with drawn patterns, similar to the patterns that the sticks will be drawing in the sand. Via loudspeakers in the other boxes you will be able to hear the intimate sounds, the sounding interior, of the inscriptions that the sticks are making.”

Is the score pre-made, or is it drawn as part of the process?

“In a way both are the case. I already drew the score, but there’s also the play of light and shadow, that continuously will give rise to new constellations.”

The moving, writing and wired sticks are the heart of the installation.

“The sticks are tapping sticks, that are sort of scanning the piles of sand and soil. You can think of them as blind man’s sticks: – ‘I am a blindfolded person walking within a landscape where I attempt to resonate everything I come across with a tapping stick. And at the same time I am a deaf person walking on the same road, trying to understand which language the landscape is speaking’ – . It is a thinking, an understanding, a grasping through listening; and then analyzing the absorbing complexity of the landscape that surrounds us. I also mean the cultural and social landscape. This image of a blindfolded person is closely related to my phonographic practice. I do a great many recordings, and I connect them to an awareness, a sensibility of places; or of surroundings and things; of the places within things. All this is quite essential for the work. Gaining knowledge through abstract listening, or gaining abstract knowledge, through the sensing-knowing-understanding part of the brain, through listening to sound and its resonance in matter. This is material memory, which is one of the most important, interwoven, concepts that I find useful for talking about my work. It is a concept that is directly linked to ‘Writings’.”

Did you ever have, or tried, to find your way blindfolded? With a blind man’s stick?

“Yes I did! As a kid I went to school blindfolded. Almost every day. A friend picked me up at home, and the game I played was that I still was so tired that it was necessary for me to continue sleeping on my way to school. My friend made this possible by guiding me. He held my arm and led me with instructions like ‘step up, step down’, et cetera. And I could hear him, for I was not really sleeping, of course. But there was no light entering my eyes. Later I also often used a blind man’s stick as a way to investigate the resonances of a spot or a space. It is a great way to get to know the acoustics of a space.”

In all of your earlier works field recordings play a crucial role. In works inside you integrated recordings made outside, in a different place and time. You are not going to do this in ‘Writings’. All of the sounds will be generated by the installation itself. There is an outside (the hole in the garden) that you can see from the inside, and an inside that you can see from the outisde, like two poles; like a negative and a positive. But once inside, the work is entirely self-contained. It is a closed system…

“It is indeed for the first time that I create a space in which everything is related to one spot and happens at this spot. As such, ‘Writings’ combines in a very direct way the two sides of my practice as an artist. That is pretty exciting, en I am very curious to find how it will work out. Because, of course, I haven’t seen it. Yet…”

[This conversation with Signe Lidén took place on March 27th, 2013.

The technical realization of the work, during the first three weeks of April 2013, will be done by Signe in collaboration with her Norwegian colleague Roar Sletteland.]

Four weeks later, in Kortrijk…

What ‘Writings’ looked and sounded like, and what had become the material form of that what Signe had imagined and described in our earlier conversation, I found out four weeks later, on April 21st, 2013, at the opening of the Flanders Festival in Kortrijk’s Sounding City.

The space in the Buda tower was filled with the low rumble and clanking sounds of the mechanics of the installation, very present, but not too loud or obtrusive. The windows were covered with tracing paper, permitting the light to fall through, but not giving visitors a chance to look out, thus isolating the work from the rest of the world. It felt like stepping into an abandoned factory hall (which I guess are fine examples of contemporary manmade caves and which, in a way, in this former brewery building, it indeed was), where a number of machines had been left working, indulging themselves in a mechanical routine, the purpose of which had been forgotten a long time ago. Six limbed sticks were being moved around by the three circular plates on the ceiling, hitting and thus, though ever so slightly, re-shaping the piles of soil below them on the floor, that, for some reason, had been left there, and by the contingency of their material substance and form now were commanding their proper tracing, for ever and ever. The amplified sounds of the sticks’ hittings and tracings could be heard inside the two pairs boxes, as through a ‘sonic microscope’. One pair of boxes was facing the brick wall of the room. The second pair faced the covered window, combining the sounds with the sight of ‘writings’, the tracings of Signe’s score (pictures of which are illustrating our conversation above), making it reminiscent of what – in Dutch – is called a kijkdoos.

‘Writings’ in Kortrijk turned out to be, in sights and sound, an atmospheric, but also a rather hermetic work, impregnated by a sense of ‘formality’ and ‘philosophy’ that seems to be teasing the visitors, asking for a sudden flash of insight, an illumination, on their part, to make sights and sounds fall into place. “Yes, it is strange,” Signe said. “Several times during these weeks of creating ‘Writings’, together with my collaborator Roar Sletteland, it felt as if nature took us by surprise. I think it is the strangest piece I ever made…”

‘Writings’ can be experienced in the Budatoren, during the Flanders Festival in Kortrijk’s Sounding City until May 5th, 2013. Subsequent installments of the work will be part of upcoming RESONANCE events, later this year.