The Bells are the Sound of the City

January 25, 2011 § 1 Comment

A visit to the city carillon of Maastricht with Esther Venrooy and city carilloneur Frank Steijns

One of the interesting aspects of Esther Venrooy and Ema Bonifacic’s installation A Shadow of A Wall is that the relatively soft and slowly changing and shifting field of sounds that Esther created, will combine with the sounds of the city that come floating in from outside. In order to emphasize that side of the work, Esther had agreed with Maastricht’s city carillonneur Frank Steijns to try and arrange for a number of specially created melodies to be played regularly on the carillon of the Maastricht town hall, maybe not all the time, but at least for a part of the duration of the Resonance exposition in the workspace of Intro in situ. That of course was a wonderful idea, for indeed, as Esther explained to the visitors of the Café In situ evening in Maastricht on Tuesday January 18th, those bells are the sound of the city.

Earlier that same day, Frank took Esther and me all way up into the town hall’s belfry, to visit the carillon and explain us all about that wonderful instrument and its history.

We passed via the town hall’s attic and from there climbed ever steeper 17th century wooden ladders, higher and higher, all the way to the open, windy and rainy top where one can find the bells. The oldest among these were among the last bells founded by the legendary Hemony brothers.

At successive stages of our ascent we came across ever more modern mechanisms for the automatization of the chiming of the bells, with hammers to strike the bells on the outside. The automatic chiming has been applied in Maastricht since 1910. From that year stems the enormous solid brass drum, the speeltrommel, made by the Dutch bell founders firm Eijsbouts.

Melodies are programmed, like on the old music boxes, by setting pins on the drum, which will begin to rotate when the drum-weight is released by the tower clock. Via a system of levers and wires, each of the pins will lift a hammer, which then falls back on the sound bow of the bells as soon as the pin has passed. (Here is a link to a detailed description of the mechanism.)

The speeltrommel was last used in 1962, by Frank’s father, who was Maastricht’s city carillionneur from 1952 until 1997. In that year his son took over. As Frank explained, the position of city carillionneur often, and still, is filled by successive generations of a same family. His father at the time succeeded five generations of another Maastricht family of stadsbeiaardiers. The speeltrommel mechanism was abandoned almost fifty years ago, mainly because of the resonance (in the big entrance hall just below) of the noise produced by the rotating drum. Frank Steijns, however, intends to have the mechanism restored. If all goes according to plan, the speeltrommel should be in working order again in 2012. Due to the mechanics involved, Frank told us, the sound of course is quite different from that obtained via the current automatic playing by means of a computer interface. The idea is to then use the speeltrommel in the evening, when in the town hall below no one will be bothered by the reverberation of the grinding sounds produced by the turning of the heavy brass drum. (You may imagine, though, that personally I am much looking forward to go there one evening with Frank in order to listen to and record precisely that sound…)

One level up we came upon yet another abandoned system for automatic chiming of the bells, also produced and installed by Eijsbouts, with – as Esther obseved – a very 1970s-like look, reminiscent of the futuristic machines we all love and know from watching too much science fiction and too many Dr. Who’s.

This one, a bandspeelwerk, is an electric relay system, operated by a broad white plastic tape in which holes have been punched, much like the book organs used for the playing of mechanical street organs. The holes here, however, are all of the same size, as the bells need just to be hit: there is no sustain, other than their resonating until being hit again.

This part of the town hall’s belfry looked as if it also served as the municipal dovecot. Which of course might be a thing of great value, as pigeons could provide the last possible reliable means of communication when in time of local, national or global disaster all other means fail. The pigeons responsible for the mess, however, were not civil servants, but mere squatters, that last summer invaded the tower, though no one actually has been able to find out how and where they managed to get in. Their presence accounts for the deplorable state of the nice little machine that is used to punch the holes in order to produce the tapes that are used to operate the bandspeelwerk.

Also the bandspeelwerk is not operational. There are also no plans to restore it, Frank told us. Not only would it be very costly to restore and then maintain, but also, in fact, each of the automatized systems uses a separate set of hammers to play the bells. Three sets indeed might be overdoing things somewhat, though I could not help getting pretty excited when I imagined the possibilities that having them opens up for a music that uses the three separate mechanisms to play the bells in three independent but simultaneous voices, and then add a manual part as a fourth voice on top…

We passed another level (where four perpendicular metal axes parting from the room’s center operate the clocks that are on the four sides of the tower) and then, from the outside came through a door in the tiny room with the carillon’s baton keyboard (the stokkenklavier), from which one more ladder leads up to the bells.

Up in the ‘control room’ Frank and Esther discussed the sounds and melodies to be played each quarter hour between 8 am and 10 pm, as part of the final week of the exposition of “A Shadow of A Wall” at Stichting Intro in situ. For this, Esther had determined five central notes, based upon the dimensions of the wooden panels used in the installation. She had written them down on the first page of a small note book, that she put on the carillon keyboard’s music stand: cis-4, cis-5, d-6 (approximately), ais-5 and cis-3.

Frank then played around a bit with these notes, by hitting the corresponding batons of the keyboard. He improvised and showed a number of possible ways of playing them, in the original sequence, or as a transposed one, with or without more or less quick arpeggio’s, simulating glissandi from one cis or fis to another… I am pretty sure that out in the city people looked up and wondered about the curious patterns of sound that suddenly came chiming down from the town hall’s belfry. It was a short foretaste of what the city would sound like every fifteen minutes on the days later this month, when the carillon would become a part of “A Shadow of A Wall”.

Of course Frank himself will not be up there every day of the week from 8 am till 10 pm, to play these melodic patterns manually. The playing will be done automatic, applying the mechanism for automatic chiming that is currently in use: a computer interface, built and maintained by bell founders Petit & Fritsen, who also provided (in 1997) the most recent bells that were added to the carillon, which currently counts 49 bells.

At the very end of our little excursion, however, it turned out there was a catch. When Frank tried to get the computer to actually play the carillon, it didn’t work. Even more so, the carillon most probably had not been playing for quite a while already. Something must have gone very wrong during the recent period of pretty low temperatures, when the hammers froze stuck, and the electronic interface continued to try to get them to play. We later learned that it would take at least four weeks before the interface can be repaired and put back in working order. Until that time the city of Maastricht will have to live without the sound if its bells. It also means that, unfortunately, there will be no quarterly melodic signals coming from the town hall carillon, to complement the sounds of “A Shadow of A Wall” for the final part of the exhibition at Stichting Intro in situ…

That’s a great pity.

Mais l’idée est bonne!

There will be other cities. The next installment of “A Shadow of A Wall” will be later this year in Kortrijk, Belgium.

There is a fine carillon also in Kortrijk.

Esther Venrooy‘s and Pierre Berthet‘s Resonance installations can be visited at Intro In Situ (Capucijnengang 12, Maastricht) until January 30th, 2011. Opening hours: Wednesday till Sunday, between 12h and 17h. Entry: €3,-.

On Sunday January 30th Peter Kiefer will talk about sound art and his recent book Klangräme der Kunst (Sound spaces of art), at Bookshop Selexyz, Dominicanenkerk, Maastricht. 13h30. After Peter’s talk all are invited to come over to the Intro in situ workspace for a drink and to visit the Resonance exposition.

Caught in the flux of history

January 11, 2011 § 8 Comments

Pierre Berthet on hitting things, Filter Queens, drops on tin cans and extending deliberately broken speakers

Liège is a major city in Wallonia, the French speaking part of Belgium. It is situated in the valley of the Meuse river near the borders with Germany and the Netherlands, at just a little over 30 kilometers from Maastricht. I remember Liège from dreary and rainy sunday mornings, when I went there with my parents to visit the market. In those days, the most curious and exotic things could be freely found and bought there: from the test tubes, Bunsen burners, mortar and pestle’s, Erlenmeyers, pipettes, tweezers, tools and bits of metal that I badly needed for my alchemical experimentations, to all sorts of old and intriguing electrical equipment, motorcycles, rusty machine guns, flamethrowers, cats and dogs and French speaking parrots. It was a slightly disturbing and foreign place, but therefore also a very thrilling one to be.

Liège is home to Belgian musician and sound artist Pierre Berthet, whose installation Extended Drops currently is part of the Resonance presentation at Stichting Intro in situ in Maastricht. Pierre’s work for me invokes an atmosphere that is not unlike the one that I recall and cherish from the strange adventures of Bram Vingerling ( † ). And from my long ago visits to the market in Liège: slightly disturbing but thrilling…

“I am originally from Brussels,” Pierre told me, “but I have been based now in Liège for about 20 years. I came there to do my civil service, at the Centre de Recherche Musicale, and then studied with Henri Pousseur, Garrett List and Frederic Rzewski. Back then the Liège Conservatory was a great place to be! I always loved sounds and I always loved music. So from an early age on I began to learn music. First at the music school, and then later as a percussionist at the conservatory. For even though I tried hard to find good alternatives, I did end up being at the conservatory… As a performer I was part of the ensemble Fusion, led by the late André van Belle’s, who used to teach at the Brussels Conservatory. Towards the end of the 1960s Van Belle began to collect exotic instruments, like gongs and chinese tam-tams. His wife played the zheng. He then put together an ensemble that could play pieces written for this collection of instruments. That was at a time when nobody yet talked about things as ‘world music’. Around the same time I learned to play the carillon, in Wavre, and Van Belle composed two carillon pieces for me. I haven’t played the carillon for a long time, though, for lack of time…”

It is an amazing instrument …

“Yes it is! Unfortunately though it is an instrument that still is too little used. It is not often used à sa propre valeur, as one says in French, in ways that really do justice to its potential.”

Your work rather early developed in the direction of… well, let me call it ‘sonic bricolage’. How did that happen?

“In parallel to my studies, I started to make music with whatever I could lie my hands on. Percussion of course lends itself very much to the use of a wide range of different objects, for, obviously, on peut taper sur n’importe quoi … you can hit anything in order to make it sound. I liked doing that so much, that eventually I found myself spending more and more time pursuing my own little musical research, and less and less performing somebody else’s music.”

Do you continue to perform as a percussionist?

“Not really, no. But sometimes people call me when something really bizarre needs to be done. Currently I am doing a piece by Tom Johnson for five sonic pendulums. These are brass bars attached to wires. They swing like a pendulum, and one has to hit them in time. The lengths of the wires have been calculated in order to account for specific polyrhythms. The piece is called Galileo, as it was Galileo Galilei who discovered the simple relationship between the length and the frequency of a pendulum. It is on this relationship that Tom based his composition and instrument. He then asked me to play it for him, for he himself is too old now. Maybe not so much for playing, but especially for traveling around with the instrument. This of course I find an honor to do. In principle anyone may play the composition. But you have to build it. The longest of the pendulums is some 3 meters and 40 centimeters, one needs something to suspend it from, et cetera. So that is not always easy. And it’s not an easy piece. It took me a full winter, to learn to perform it by heart.

I think that your training and background as a percussionist do show up quite clearly in your performances sound installations. Percussion and rhythm are obviously at the heart of the dropping of the drops in “Drops”. But also the vacuum cleaner pieces I find very ‘percussive’ in nature. There is the fierce – almost agressive – sweeping of the tubes along the floor and…

“But that’s all mostly wind blowing, I’d say… No?”

Maybe it’s just my peculiar way of hearing, but I do experience much of it as ‘rhythmic investigations’. For example the vacuum cleaner installation you did for the 2008 Best Before Klankkunsttour in Maastricht. Or the performance that you did later that year at Stichting Intro. The vacuum cleaner, by the way, is one of the elements in your work that over time continue to recur, again and again, always in different constellations. What was it that originally led you to the vacuum cleaner?

“I was asked to do the music for Баня (The Bathhouse), a theater play by Mayakovski. This was the last piece he wrote, before committing suicide. It deals with the Soviet philistinism and bureaucracy. So the décor shows offices and all kinds of office material. I then tried to sonorize that stage scenery, making music with office cabinets, with papers, and the like. And part of the décor was a vacuum cleaner of the marque Filter Queen, which can both aspire and blow. That’s where it started. Also, there is sort of a tradition in the use of vacuum cleaners in contemporary music and art, isn’t there? And did you know that Captain Beefheart used to worked as a door-to-door Filter Queen salesman? Or maybe it was another marque, but he has been selling vacuum cleaners for a while…”

Oh, really? That’s interesting. He was at high school together with Frank Zappa, and my first encounter with a non-standard use of vacuum cleaners must have been in some of the earlier Frank Zappa work. But I think that Zappa was mainly interested in the erotic potential of the vacuum cleaner as a sucking machine, not so much in the sounds it makes… Are you a collector? Of vacuum cleaners? I always see an awful lot of them lying outside with the garbage, in the streets of big cities. And you? If you’d see one, would you take it?

“No, no, I buy them! There is a shop in Liège that specializes in Filter Queens. The specific type that I use is no longer made, but the shop collects and repairs old ones. I now have five of them. These form my current ensemble. And they are pretty solid, really. The motor may wear out, though, also because of the pretty rough stuff that I make them do. For many years I had just a single one. But now that I have quite a few of them, I can also use them in installations. Then their functioning is automatized. The only thing that is a bit complicated, is that once has to assure oneself that when it starts, the sweeping of the tube will not be blocked. So the floor has to be pretty smooth. If it is not, there has to be someone around to unblock them every now and again. That’s the drawback of these ‘automatic installations’. But, on the other hand, the fact that the things are not completely stable and somewhat imprecise of course also is part of the charm of the ‘bricolage’.”

“So the vacuum cleaner is one of these elements that I continue to come back to. Like the drops, like the extended speakers … Because … well, I just do not have that many ideas, really. So I re-do the old ones …”

But there’s always a development? It is not just a matter of merely re-making the same, is it?

“Well, it is rather that the things develop all by themselves. I often say to myself: ‘Okay, now let me do this one or that one again’ … But then, when I try, I find that I am actually not capable of doing the same thing over again. And so it becomes something else. That is because the way all of it is put together is much too unstable. Nothing is very precise, and the things are not exact enough to be reproducible. And because I am not capable of reproducing that what I did before, the works end up showing a development over time.”

In the Extended Drops installation – that you originally set up for the Singuhr Hörgalerie in Berlin, and that now you have adapted for the workspace of Intro in situ – you combine two other recurring elements from your work: the “Drops” and the “Extended Speakers”.

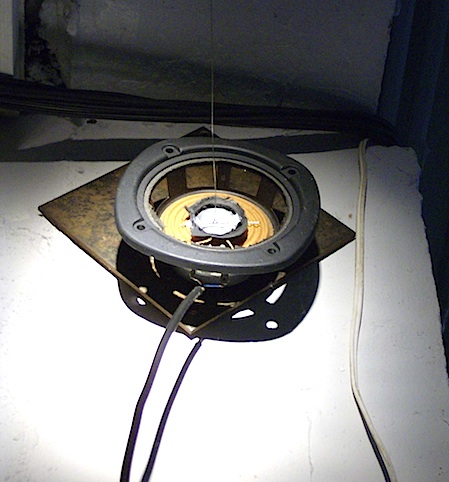

“Yes. It is already for some 30 years now that I have been letting drops of water fall on suspended tin cans, from a height of about 2 meters. And also, for 15 years or so, I have been breaking loudspeakers, by removing as much of the membrane as possible (in order to hear them as little as possible). And then I attach thin steel wire to the remains. The other end of the wire I attach to a net of steel wires, each of which ends in a resonating can. These cans are then distributed over the space. The loudspeakers are no longer used for playing back sounds. They are used to make this net of steel wires vibrate. So the net of wires with the resonating cans extend the loudspeaker. That is why I call them ‘extended loudspeakers’. Usually I then apply sine frequencies as a sound source. But the sounding result is something completely different.”

How do you decide what frequencies to use?

“I try. It will depend on the specific space, which determines the lengths of the wires that I use. So once the network has been put into place, I try it out. And then I will use those frequencies that I like best. With these I create a short sound piece. Depending on the place in the space where I put the resonating cans, the length of the wires will vary. And so will their natural frequencies. That takes a little bit of searching and testing, though in practice it turns out that almost anything will go. And then, once I have chosen the spots, I have obtained a certain ‘palette’ of sounds. Next the work is a bit like that of painter, who is using the divers colors that he has available to fill his canvas. Which in this case is the given space and a certain span of time.”

So the result is actually a composition for the extended speakers in that particular space?

“Yes. Often what I end up with are a certain number of loops, which I then play back from the computer. And in ‘Extended Drops’ I combine the ‘extended speakers’ with ‘drops’. This was partly inspired by a work of the French sound artist Arno Fabre, that I heard about, though I never actually saw it. It is an installation called Composition pour trois radios. He lets drops of salted water fall upon the cut loudspeaker wires of the radios. When a drop of salted water falls upon the wire, it briefly re-establishes the contact and thus one briefly hears a sound. “

The drops act like a switch…

“Exactly. The description and pictures of Arno Fabre’s installation gave me the idea to adapt the same principle to my extended speakers. So I add a bit of chloridic acid to the water, which then drops onto the cut wires. From there it drops on, into the tin cans below. These now are somewhat bigger than usual. I want to make sure that they make a sound, as I have contact microphones attached to them. The sound may be sent back into the extended loudspeakers, but the main function of the piezo’s is that they enable the computer to ‘hear’ the rhythm, the frequency, of the drops. Thus we can instruct the computer, for example, to release 60 drops per minute. The computer then commands a number of small servomotors that open the tubes more, or less, in order to have the drops fall faster, or slower. But there will always be a certain irregularity in the rhythm of the drops. For example, let’s say that the computer needs to arrange a rhythm of one drop every four seconds. It will tell the servomotors to open the tubes more, or open them less, and this adjustment will take some time. Thus the drops will not fall synchronously everywhere. This accounts for the complex rhythmic patterns that you hear.”

Visually the installation gives the impression of something quite simple, something purely mechanical. But it actually takes rather sophisticated digital steering to make it tick.

“For this I have the help of Patrick Delges, who also is living in Liège and with whom I have been collaborating already for a number of years. Patrick does the programming in Max/MSP. It enables us to program transitions. So, for instance, we can ask that the frequency increases from 60 drops per minute to 80 drops per minute, over a certain period of time. Apart from that, there are a number of other ‘drops machines’, that do not activate the loudspeakers. These just let drops fall into small tins.”

And you pass every day to poor the water from the tins?

“We use two tanks of 70 liters … but, yes, some regular emptying and filling work needs to be done …”

Do you think of yourself as a sound artist, Pierre?

“I rather think of myself as a musician. I do not wake up in the morning saying to myself, ‘OK, now let me do some sound art…’ But I am very interested in the history of the ‘discipline’. I also like to follow what other artists in the domain are up to… So… talking about sound art, yes, I guess I do find myself being caught in that particular flux of history.”

On January 18th, 2011 Harold Schellinx will talk with Pierre Berthet and Esther Venrooy about their work, about music, about sound art and its relation to the world, to time and to space, in Café in situ (Intro in situ, Maastricht). The evening starts at 20h30.

Pierre Berthet’s and Esther Vernooy‘s Resonance installations can be visited at Intro In Situ (Capucijnengang 12, Maastricht) until January 30th, 2011. Opening hours: Wednesday till Sunday, between 12h and 17h. Entry: €3,-.

[ ( † ) Bram Vingerling is the protagonist in a series of Dutch (and, as far as I know, never translated) mystery novels for teenage boys, written by Leonard Roggeveen. Roughly from the 1930s up to the early 1970s, the Bram Vingerling books (a fine brew of patriotism, mystery, heroism, morality, technology and science) were very popular in the Netherlands. ]